by Finn Lefevre (they/them)

Long sleeves, cover my tattoos.

In 1962, article 489 of the Penal Code officially criminalized queerness in Morocco.

In 1962, article 489 of the Penal Code officially criminalized queerness in Morocco.

Hair pulled back, no makeup.

Since then, countless LGBTQ+ Moroccans have faced harassment, fines, and even prison time.

Head down, hands in my pockets.

Trans people have been especially victimized, often with little distinction between gender identity and sexuality in public policy, and numerable incidents of anti-trans violence.

Voice low, bite my tongue.

I came to this country having researched this history, ready to perform a kind of masculinity I thought would be more palatable.

Stop talking about my husband. Stop talking about my husband. Stop talking about my husband.

I got advice from everyone—locals, guides, organizers, and expat friends.

Maybe I should wear less pink.

Only part of me visited Morocco. I didn’t bring my full body, I didn’t bring my full self, I didn’t even think I could.

Pronouns? Forget it.

But I’ve never been a very good actor, and this role in particular never fit quite right.

There are two Moroccos.

One is what we know—the discriminatory laws, the overwhelmingly negative public opinion, the stark lack of resources for LGBTQ+ rights.

But the other Morocco is here too. The other Morocco is queer. Quietly, maybe, but still vibrantly, gorgeously queer. And I want everyone else to see what I saw.

In 1962, article 489 of the Penal Code officially criminalized queerness in Morocco.

In 1962, article 489 of the Penal Code officially criminalized queerness in Morocco.

I saw it in the laughing men who drove the pink princess cars in loops around the riverwalk in Casablanca, something I wasn’t brave enough to try for fear of judgment.

I saw it in the punks that skirted the edges of the crowd after the Morocco-Portugal World Cup game in Rabat, with their piercings and tattoos and torn Blondie tank tops.

I saw it in the way Moroccans greet one another—a gentle allowance of touch between men that would be received so differently in my home country.

But most of all I saw it in the art.

I’m an artist, theater mostly, but like many artists, I dabble across media. I’m no stranger to coded queerness in art, and my eyes are trained to hone in on these small gestures, these hidden messages. The coding is different here, so maybe what I see is only queer in my eyes. But it’s still here.

I saw it in the boy with flowers painted on an apartment building, and I wondered if the people who lived there saw it too.

I saw it in a self portrait of an artist titled “I can’t see me anymore,” and I nearly cried at the words, because just that morning I’d told my husband I was homesick for my own body. For my own clothes, my own makeup, and my own way of moving.

I saw it in a portrait with no title, Moroccan patterns erupting from between the genderless figure’s thighs, consuming them.

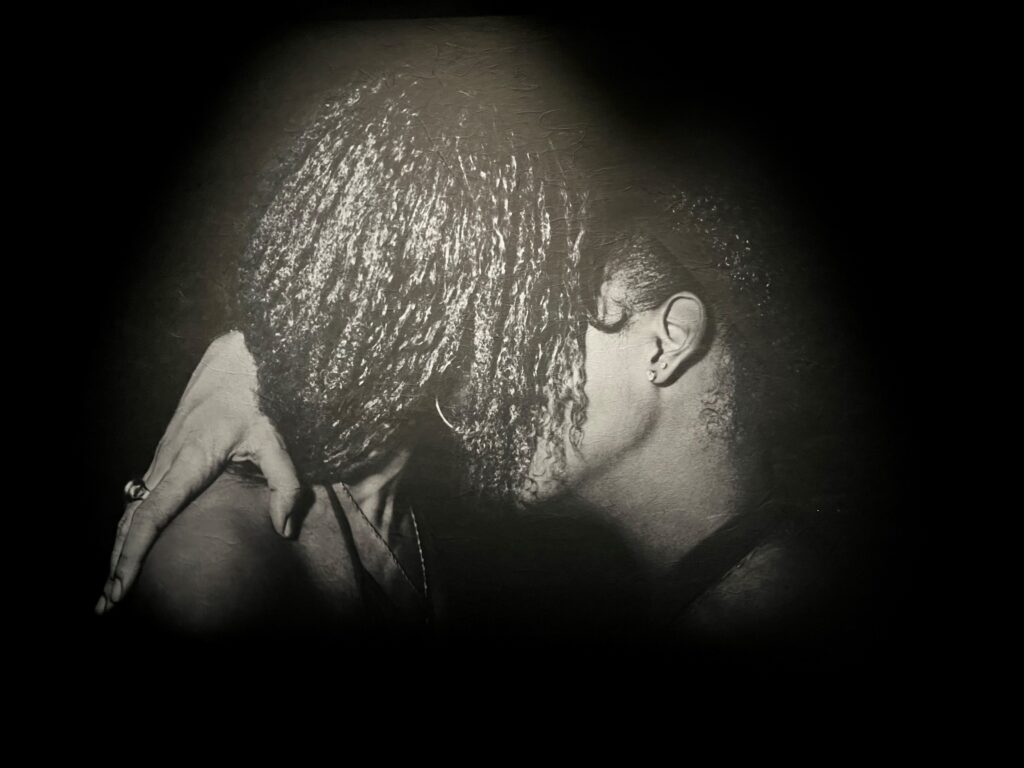

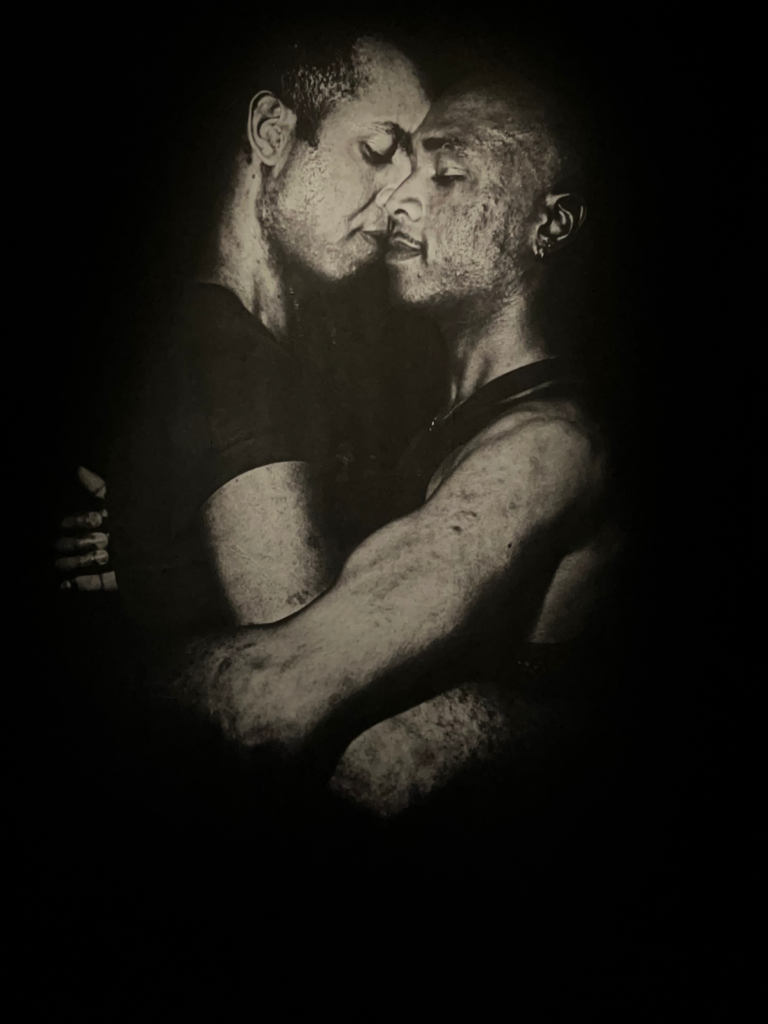

And then I saw it in a labyrinthine photography exhibit, the lightless room spiraling around itself, such an impossibly private experience created in a public exhibition.

The artist behind these photographs, Touhami Ennadre, works in shadows as much as his subjects—small, private glimpses of life cutting through inky blackness.

The exhibition, QASIDA NOIRE at the Mohammed VI Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, is a first of its kind. The fellows and guides I spoke to said they’d never seen anything like this at a public art gallery. Queer images exist, of course, a fellow tells me, but never this exposed.

I feel exposed just seeing the images.

I feel like Ennadre has wrenched my soul out and placed it on dark walls for anyone to see. But not anyone will see it, I’m sure. It’s not on the street, it’s not on TV, it’s not even advertised as queer subject matter. But it’s here. Simple, evocative images of intimacy, of love, of connection. Of queer Moroccans.

I feel like Ennadre has wrenched my soul out and placed it on dark walls for anyone to see. But not anyone will see it, I’m sure. It’s not on the street, it’s not on TV, it’s not even advertised as queer subject matter. But it’s here. Simple, evocative images of intimacy, of love, of connection. Of queer Moroccans.

Seeing this exhibit gave me so much hope, so much excitement. This is new for Morocco, this is boundary pushing and world shifting in its own, soft way. It’s not the raucous celebration we joined after winning a game in the World Cup, but it’s still a celebration. It’s not the loud & bright pride parades in my home state, it’s a different way of making space for queerness. There is so far to go, but I feel like I was given the chance to bear witness to one big, beautiful step towards being seen.

So next time I’m in Morocco, maybe I’ll let them see me too.

https://fnm.ma/exposition-touhami-ennadre-qasida-noire-au-mmvi/

All opinions expressed by the program participants are their own and do not represent nor reflect official views from the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs of the U.S. Department of State, or of the Institute for Training and Development, Inc.